I’m one of about half a dozen people in the world who doesn’t like Sherlock. I started out with an open mind, missed a few episodes, and then returned last night during a period of consciousness between bouts of jet lag. If this were an adaptation of any other character from literature, I probably wouldn’t mind the liberties that have been taken with him. But Holmes is a national treasure – and the BBC has stolen and vandalized him. In their brazen effort to compete with other eccentric exports like Downton Abbey, they have retooled him for the US market. Like much of British TV, the result is an ugly chimera of different styles – melodramatic, camp, gaudy, and inconsequential. The quiet intelligence of the source material is completely lost.

Historically, the difference between British and American detective stories has always been this: the British are interested in how someone was murdered, the Americans in why.

The average Agatha Christie novel is a mental puzzle. Someone dies improbably, red herrings are introduced, clues are dangled, and the killer is unmasked. There is little emotion involved. In contrast, the great mystery fiction of the USA is motivated by the human drama surrounding the kill rather than the kill itself. Raymond Chandler’s novels were so disinterested in the mechanics of crime that he confessed that he didn’t know who murdered the chauffer in The Big Sleep. His detectives were flawed human beings who often got it wrong. The thrill of Farewell My Lovely – for my money, the greatest noir ever written – is neither the murder (we never see it) nor the unmasking of the culprit (which surprises the hero as much as us). Likewise, the novels of Ed McBain are more violent pornography than they are criminal fiction, while Dashiell Hammett is just as keen to expose the hypocrisies of capitalism as he is a murderer.

The differences between these two traditions reflect the differences between our two cultures – or at least they used to. It was once the case that British society was mannered and cerebral, while Americans were more tactile and human. Compare Father Brown with Mike Hammer and you’ll see what I mean.

In the last twenty years, British culture has lost a lot of its Anglo-Saxon restraint, which is why I find watching the BBC drama Sherlock painful. Sherlock Holmes is the most intellectual detective of all. In fact, he pretty much set the standard for the English obsession with the nuts and bolts of detection. It’s not true – as the TV series labors – that he guessed everything from a mustard stain on a lapel. Aside from pioneering forensics, he was also a master of disguise and tasty with his fists. He wasn’t excessively rude (I don’t know why Sherlock has turned him into a morose teenager with undiagnosed autism) and he often expressed admiration for feminine pulchritude. He was not gay and he certainly did not have a thing for Moriarty – a character who he met only once in the novels.

In the hands of producer Stephen Moffat, however, Sherlock is a very modern young man. His relationship with Watson has been elevated (or lowered) to platonic love affair. He has a past and a complex relationship with his brother. He hates the world – or does he love it, we cannot tell? – and he desires competition above all else. He is young to the point of hip. The “Bohemian” lifestyle alluded to in the books is here a student digs with psychedelic wall paper. This is the BBC, so our hero cannot possibly smoke. Instead, he wears nicotine patches.

Ignore the endless references to Holmes’ “genius” played out in the show: Sherlock is not a British puzzle, it is an American soap. The absence of intellectual gameplay is reflected in the fact that Moffat will often crowbar several Holmes stories into one episode. The care and attention that Doyle put into explaining how the “impossible” could be made “plausible” is gone. It is replaced by fast paced camera work and high-tech graphics. A kidnapper is identified by the soles of his feet in ten seconds – Huzzah! – allowing the pre-pubescent Sherlock to move one step closer to unmasking Moriarty, the overacted criminal mastermind who, let us not forget, he only met in one Doyle story!

To disguise the lack of plot between each set piece, the director makes his cast run around a great deal and occasionally sends the camera zooming up the actor’s nose. But visual tricks aside, Sherlock is an exercise in character study – and this should come as no surprise. Stephen Moffat is one of the villains who also corrupted Dr. Who. He helped turn a science fiction show aimed at kids into Coronation Street in Space, replete with histrionics, gay kisses, regional accents, brassy women, and special guest stars of the Ken Dodd variety. As with crime fiction, science fiction is technically all about ideas. But Dr. Who’s producers have replaced those ideas with a by-the-numbers drama about human relationships. Will the time travelling doctor ever find love? Do any of us really care? Aside from an admirable taste in bowties, he strikes me as a gurning simpleton.

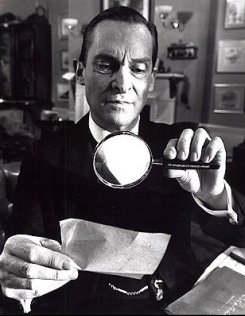

We once did crime so well. The 1980s were a golden age of TV detectives, all loyal to their textual source. For my generation, Sherlock Holmes is Jeremy Brett (yes, I know that some of his later stories weren’t Doyle’s) – a man so obsessed with capturing the character of Holmes accurately that it actually drove him mad. Likewise, Joan Hickson’s Jane Marple was spot on – down to the lady’s cold stillness, her ability to detect evil at a glance over a tea cup. These shows usually took one story and stretched it out over 2 hours, or several weeks of shorter episodes. They were long, languid, and gorgeous. They were also very sad. The joy of English conversation lies in what is unspoken rather than what is said. We scream at each other in silence. It takes time and care to evoke that kind of pain.* The whizz-bang, cinematic rollercoaster of modern television cannot do it.

I don’t intend this to be read as a condemnation of American culture. On the contrary, I’m as home in the world of pulp as I am on Baker Street. But rather it’s a lament for the fact that the British seem to have forgotten how to do that which we used to do uniquely and so well. The English ability to blend complexity with understatement – to say a thousand words with one handshake – is leaving us. We are not the people we once were. Nor, I fear, shall we ever be so again.

*Consider how well it was done in the Brett version of The Final Problem.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed